North Pole Photos and Expedition Journal

Posted by Ingrid Nixon

in Expeditions and Polar Regions

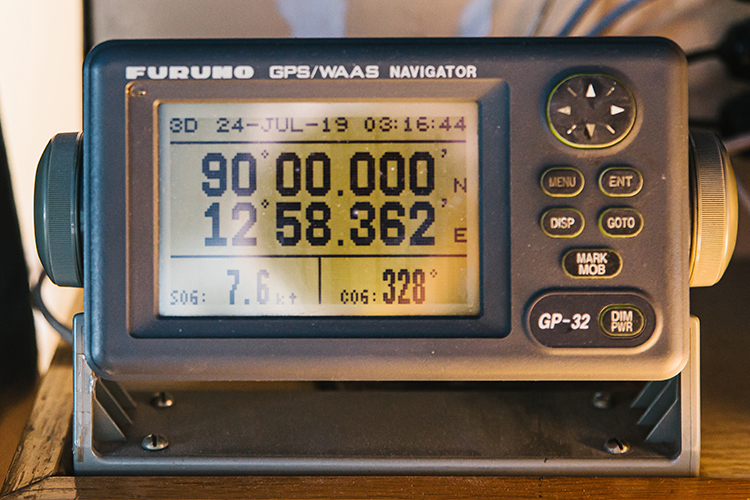

In July 2019, Apex explorers traveled aboard the world’s most powerful nuclear icebreaker, 50 Years of Victory, slicing through pack ice to reach the very apex of the Earth—90° North. Field leader and professional storyteller, Ingrid Nixon, reports here on some of her most profound memories and shares her North Pole photos from Apex Expeditions’ first journey to the top of the world!

The Most Powerful Ship on Earth

The 50 Let Pobedy (or in English, 50 Years of Victory) is quite possibly the most powerful ship on Earth. Completed in 2007, she is a working ship for about ten months of the year breaking ice over northern Russia. During the summer she works under charter for North Pole trips. Her innovative spoon-shaped bow makes her very good at breaking ice and “under the hood” she has two OK-900A nuclear reactors that power two steam turbogenerators. At 524 feet long, 98 feet wide and 25,000 tons, she can cut through 2+ meters of ice with barely a shudder, as we would soon discover.

Our North Pole adventure began in Murmansk—home to Russia’s nuclear icebreaker fleet. We met our first iceberg on our first day at sea, cruising north through the Barents Sea. Our plan was to sail north, pass through the Franz Josef Land archipelago for a bit of wildlife viewing, then press on to the Pole. Then, after achieving the Pole, cruise south with a bit more time at Franz Josef Land before returning to Murmansk.

Crushing Through the Ice to the North Pole

To see the ship effortlessly churning through the seemingly endless sea ice from the helicopter brought home just how powerful the vessel was. The ship has one helicopter, which it uses for ice reconnaissance but we used it for sightseeing. We all made it up for two flights during the trip: the first was to see the ship plowing through the polar pack. The second flight was a short foray over the glaciers of Salisbury and Champ islands in Franz Josef Land. This opportunity for a birds-eye view is one typically only available on icebreakers, adding a fascinating dimension to the experience.

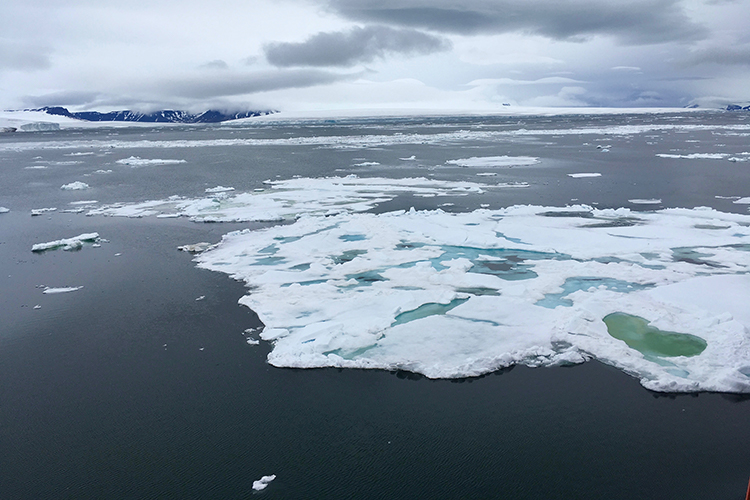

The sea ice is like a thin skin over the Arctic Basin, which is 5,450 meters (17,880 feet) deep. Traveling north we encountered one-year ice, perhaps a meter or more thick. As we got farther north, we encountered multi-year ice at twice the thickness or more. Pressure ridges formed where the ice floes jammed together, forming icy walls five meters or more thick. These were the nightmares for Arctic travelers on dog sleds, like Robert Peary and Frederick Cook. But the ship just pushed through most of them like a hot knife through butter. When we did encounter a more-resistant-than-expected bit of ice, the ship would smoothly slow, eventually coming to a halt. It would then reverse a distance, before proceeding ahead with a little more speed, which could be interpreted as determination. Only as we neared the Pole did our conflicts with the ice become more jarring, marked by one memorable meal in the dining room where silverware and glasses freely migrated around the table due to the vibration.

An Extraordinary Day at the North Pole!

July 24, 2019: 90° North, achieved in the wee hours, called for champagne and dancing on the foredeck. Others found a quiet place to contemplate the ice. To think this was the point men had striven to reach for centuries, enduring terrific hardships; risking death and many losing the gamble—it was all a bit humbling, having arrived in such relative luxury. But no matter how one thought of the experience, the agreement was that after this, it was all “south.”

Part of getting to the Pole is the ceremony on the ice, which took place south of the actual Pole as we needed a large safe floe for all of our activities. The ship jammed into a floe, put down one anchor on the ice, and put down the gangway. First things first: After disembarking the vessel we formed a circle around the ceremonial 90° North Pole and held hands as we observed a minute of silence. Then the Apex gang met by the anchor to toast the occasion with Shackleton whisky brought especially for the occasion by Jadwiga and Steve Markoff. Afterwards, we all scattered—some to do the Polar Plunge, others for photos and more exploration on the ice. After a barbecue on the ice, we all went for a hike that looped out from the ship, climbing over and around hummocks on the ice, sipping fresh water from the melt water ponds, and keeping a wary eye out for Polar Bears. At last we boarded the ship and continued south, each pondering the significance of the experience in an icescape only ever seen by a few.

An Extreme and Ephemeral Experience

It is an odd sensation, thinking of how we stood on a thin skin of ice over several miles of frigid ocean. (The ice felt solid enough.) The polar ice pack is constantly on the move driven by winds and currents. This fact vexed early explorers, who had to try to compensate for the drift on their pushes north. Norwegian explorer, Fridtjof Nansen, tried to use the drift to his advantage during his Fram expedition (1893-1893), allowing his ship to be caught in the ice and drawn north with the current. But when he calculated his ship would miss the Pole, he made a dash north, reaching 86°14’ N—a record. Some still debate if it was the Americans, Robert Peary or Frederick Cook, who first reach the Pole in 1909 and 1908 respectively. Their documentation raises questions. Many believe that Brit Wally Herbert was the first person to stand on the North Pole during his polar transit from Alaska to Svalbard in 1968-69. Perhaps it is best the ice at the Pole is ever shifting, thus preventing the build up of human detritus indicating “I was here” in multiple languages. Though it is compelling to think just where we were on the planet, the experience is ephemeral. As Sir Wally said: To put your foot upon the Pole “is like trying to step on the shadow of a bird that’s circling overhead.”

For the Most Brave Among Us

The water temperature was -1° C, which made the Polar Plunge not for the faint of heart—literally. The ship’s doctor stood by with the defibrillator, just in case. Luckily his services went unused. Near the stern of the ship, the ship’s crew cleared the ice from a patch of water for the event, which is also a great spectator sport. In all, over 40 passengers disrobed on the green Astroturf, dawned the waist belt tether and plunged/flipped/slipped into the water that was slightly below regular freezing temperature. Those who plunged talked of the surreal quality of the dip—the surface of the skin went numb, but the muscles moved as commanded underneath. With hot showers nearby, the chill and chattering teeth post-dip mattered little. Tick that one off the bucket list!

Polar Bear Sightings

“Where are they going?” came to mind with each Polar Bear sighting. We encountered our first bear in the wee hours our first night in the pack ice. A creamy yellow loner, it moved toward and around the ship, then away before sinking to its belly on an ice hummock. There would be more bears in our future. Out on the ice the bears hunted for one thing: seals. Yet we saw few seals deep in the pack ice, which made one’s stomach growl in empathy as bears moved restlessly by. The ship was probably interesting looking to them; good smelling, as well. Each maintained what it felt was a safe distance. In our warming climate it will take more than distance to protect these bears that rely on the sea ice as a hunting ground. One evening we encountered a mother with two cubs, all three sporting rounded bellies, indicating she was a good provider. But would she be good enough to bring both cubs to adulthood, a two-year commitment? Time will tell. Time will tell for all of us.

Spotting Walrus in Franz Josef Land

A group of walrus is called a “huddle.” How appropriate, given they are “positively thigmotactic”—which means they love to touch. And so we found them cuddled up with one another on the ice floes around Franz Josef Land. As the big males and females only come together during the mating time, we likely saw females and calves, and young males. Regardless, it was a lot of blubber. Franz Josef Land is one of THE best places in the Arctic to see walrus, populations of which have recovered since they became protected in 1952. The persistent sea ice of Franz Josef Land helps, too, as walrus use the drifting floes in between feeding forays as resting platforms as well as free rides to new feeding areas.

They are fiercely protective of their young, with all adults coming to the defense of a little one should a Polar Bear get any ideas. One mother swimming by with her calf seemed to shield the calf from the ship with her body and wrapped a flipper around the calf to dive. There is something comically charming about this creature, whose Latin name, Odobenus rosmarus, means “tooth-walking seahorse.” Fat, lumpy, and stumpy on ice, they prove most graceful in the water, and are yet another wonder of the Arctic.

Conundrums and Tiny Miracles

Champ Island, part of the Franz Josef Land archipelago would be a good candidate for an unsolved mysteries show. The conundrum? Perfectly round sandstone rocks abound on its landscape. Big ones; small ones; but many, many perfectly round ones and no one is quite sure how they form. Sea ice moved away from the landing, allowing us to go ashore to hike among the spheres, which varied in size from that of a car to that of a pea. No matter how they came to be, they fascinate. This was also our chance to enjoy the brilliant color of the Arctic wildflowers, which abounded on this otherwise sterile outwash plain. Beautifully adapted to the far north, Arctic plants and their pollinators make the most of the short growing season—developing a bit more each year until they can actually set seed. They are, in effect, tiny living miracles in a strange land of stone orbs.

Traveling South

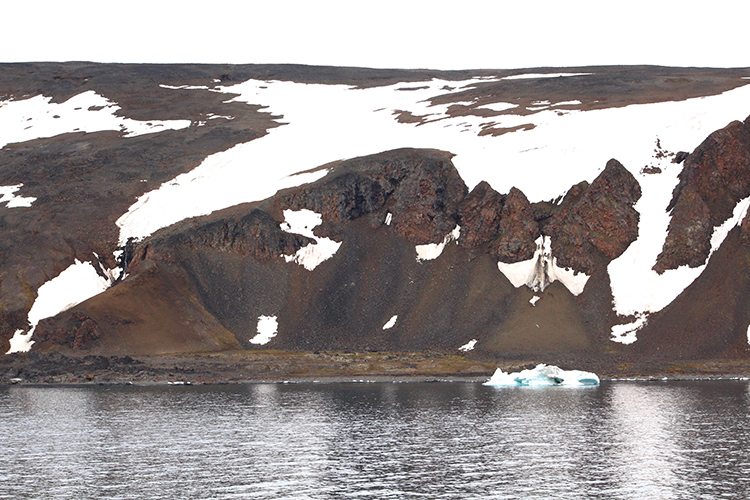

Heading south from the Pole we followed our track in the ice as much as possible, which meant that whereas it took three days to get north, we got south to FJL in two. Through the mist we saw a cliff of dark rock: Cape Fligely, the farthest north point of Rudolph Island, the farthest north point of the FJL archipelago, and the farthest north point of Europe. The captain brought the bow of the ship right up to the dark cliffs, home to Black Guillemots, Glaucous Gulls, and kittiwakes. Squadrons of Brünnich’s Guillemots zoomed by. The cliffs, like a marvel of diversity given the reduced number of species we had experienced in the ice. (Our most common companion on the trip: Black-legged Kittiwakes.) The cape was named by Julius von Payer during a grueling push north on the 1872-74 expedition that discovered the archipelago. This bluff is 911 miles from the Pole. And strangely, there was a time when this point would have felt so far north. But on this day it felt so far south.

Franz Josef Land Discoveries

A storm brewing in the Barents Sea meant we had to change plans for our last landing. Instead we would be sailing south between Hall and McClintock islands, which would take us past historic Cape Tegetthoff. The cape has two distinct pointed rock outcroppings, like stone fur seals with their noses pointed skyward. It was named for the ship of the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition led by Karl Weyprecht and Julius von Payer. In 1872 when the Admiral Tegetthoff got stuck in the ice shortly after leaving Tromso, Norway, it drifted north into unknown regions, eventually taking them to within sight of the Cape. New land! They promptly named the land—whatever it was and however extensive it was—for their emperor: Franz Joseph I. Payer made several sledging trips to explore what he determined to be an archipelago, making his way all the way north to Cape Fligely. Eventually, they abandoned their ship in the ice, dragged their two boats well over a hundred miles to the ice edge and sailed to Novaya Zemlya where they were rescued by Russian fishermen. They returned to Vienna as heroes in 1874.

Two Polar Explorers Brave the Winter

It didn’t look like much: a small beach on the southwestern end of Jackson Island. The ship nosed closer so those with binoculars could make out ruins of a small stone wall, as well as two logs. The beach, known as Cape Norvegiya (Norway), served as the “home” for Fridtjof Nansen and Hjalmar Johanson the winter of 1895-96. Having left their ship, Fram, in March to continue its drift in the ice, Nansen and Johanson made a push toward the Pole using dogs and sledges. But with summer waning and the Pole still distant, they turned south with the goal of getting to Franz Josef Land in hopes of meeting up with an expedition that could carry them south.

Winter forced them onto this small beach, where they built a shelter. The driftwood we could see, excavated by Johanson from the frozen beach with patient chops of a “microscopic little axe,” served as the beam that supported the roof made of walrus hides. So often when visiting historic sites it is difficult to figure out exactly where something occurred. Yet, no question: this was THE spot where two polar explorers huddled together in a very small space through a long Arctic winter, sustained by bear and walrus meat, planning their next move. They dared not spend too much time outside risking injury or, very practically, wearing out their gear and clothing that they would need for travel the next spring. When weather improved the two pushed on, eventually finding rescuers on Cape Flora.

But here at the beach one can imagine at Christmas that cold miserable year, Nansen, after much thought, turning to Johanson and suggesting that with all their time together, perhaps they should consider that the time had come that they should call each other by their first names.

Explore More

Read more from Ingrid Nixon and her expedition to Franz Josef Land. Be sure to check out our expedition calendar for upcoming trips to the Arctic region.

Wonderful trip lead by Kevin and Ingrid.

It was the trip of a lifetime