The Boulder Jewel, amongst the most striking of all damselfies, is endemic to South Africa. When approached by females, territorial males perform a spectacular leg-waving dance low over the water. © Jonathan Rossouw

A pair of Common Citrils demonstrating pre-copulation, the first stage of the mating process, in which the male grasps the female behind her head using his primary claspers. © Jonathan Rossouw

The Tropical Bluetail is Africa’s commonest representative of a group of around 70 damselfly species that occur widely around the world, from Australia to North America, where they are known as “forktails”. © Jonathan Rossouw

The Odonata are voracious predators of insects, including other dragonflies. Here a female Tropical Bluetail eats the abdomen of another Tropical Bluetail, while mating! © Jonathan Rossouw

A pair of Tropical Bluetails locked in the “heart position”. © Jonathan Rossouw

The dazzling Swamp Bluet prefers still water habitats, such as slow-flowing rivers, lakes and ponds. © Jonathan Rossouw

Sailing Bluet males have the peculiar behavior of landing on the water surface and drifting with the wind, or “sailing”! © Jonathan Rossouw

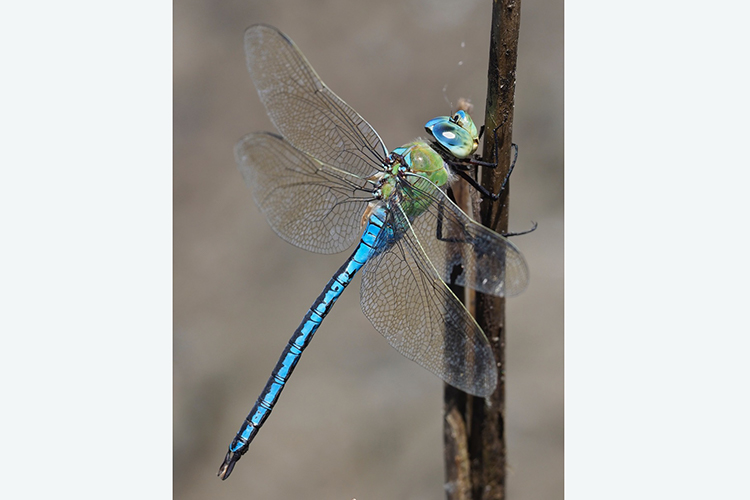

The glorious apple-green and turquoise Blue Emperor is one of the world’s most striking and instantly recognizable dragonflies, usually seen coursing back and forth over wetlands and only rarely perching. A highly mobile species, it rapidly colonizes ephemeral waterbodies and has even reached the remotest islands of the Indian Ocean! © Jonathan Rossouw

One of the largest of all dragonfly families, with almost 1,000 species worldwide, the Clubtails are immediately distinguishable from all other dragonflies (but not damselflies) by having eyes that do not join on top of the head, as demonstrated by this Common Tigertail. © Jonathan Rossouw

As is typical of most Clubtails, the Common Thorntail is solitary, shy, and difficult to approach. © Jonathan Rossouw

The name Clubtail derives from the tendency in many species to broaden near the tip of the abdomen, often with accompanying “foliations”, as in this Rock Hooktail. © Jonathan Rossouw

An Eastern Blacktail scans the skies for predators and prey. @ Jonathan Rossouw

In most Odonata, the sexes are similar in size but, as shown by these male and female Yellow-veined Widows, differ in color, body markings, and wing patterning, with the male usually more vividly colored and strikingly patterned. @ Jonathan Rossouw

Female Yellow-veined Widow. © Jonathan Rossouw

As familiar, eye-catching and widely distributed as the Red-veined Dropwing, the Broad Scarlet is easily separated by its broad, flattened abdomen and yellowish pterostigma, or wing spots. © Jonathan Rossouw

The dashing Jaunty Dropwing is a denizen of faster-flowing streams with vegetated margins. © Jonathan Rossouw

The Red-veined Dropwing is one of Africa’s most ubiquitous Odonates, being abundant and widely distributed from the southern tip of Africa to Europe and the Middle East. @ Jonathan Rossouw

The Violet Dropwing is a glamorous species favoring well-vegetated margins of tropical wetlands in the savanna zones of Africa. @ Jonathan Rossouw

The Malachites are a group of large damselflies with metallic green and yellow thorax markings, and the males of some species, such as this White Malachite, having striking wing bands. Unlike other damselflies, they typically perch with their wings spread. @ Jonathan Rossouw

Damselflies, like this endemic Goldtail, differ from dragonflies in having significantly more slender abdomens, eyes that are widely separated, and, on landing, their wings are closed behind them (as with almost all things in biology, there are exceptions, of course!). @ Jonathan Rossouw

The cryptic Horned Rockdweller is a localized dragonfly which has a highly specialized breeding habitat of potholes in large granite exposures along fast-flowing rivers. @ Jonathan Rossouw

Dragonflies are excellent bio-indicators of water quality because they rely on high quality water for larval development. The Palmiet River in Kogelberg near Cape Town is a prime example of a pristine aquatic system, and is home to over 60 species of Odonata. @ Jonathan Rossouw

Jonathan Discusses Dragonflies and Damselflies

In this article, Apex cofounder Jonathan Rossouw explores the amazing world of dragonflies and damselflies and shares some fascinating facts and photographs of these unusual insects.

Of Damsels & Dragons: Distraction in the Time of Covid

It’s an understatement to say that COVID-19 has presented challenges to all of us. As an international wildlife expedition guide accustomed to the constant intellectual stimulation of perpetual peregrinations, staying semi-sane during this “pandemic hibernation” has certainly required some mental acrobatics! This past summer, as the second wave of our local epidemic raged, I unexpectedly found welcome distraction in one of Nature’s micro-spectacles, right on my doorstep: the incredible Odonata!

The Odonata are the group of insects that we commonly know as dragonflies and damselflies. An ancient lineage with its evolutionary roots deep in the Permian, 100 million years before the first dinosaurs, they number about 6,000 species worldwide. Often brilliantly colored in shades of red or blue, and with dazzling aerial capabilities, their lively antics enrich any visit to a river, lake or pond.

A closer look reveals the unique features of these fascinating animals. Like all insects, their bodies are segmented into a head, thorax and abdomen, with three pairs of legs and two pairs of wings, along with a pair of antennae. Unlike their closest relatives, the mayflies, however, these antennae are very short, which means that they lack any sense of hearing or smell, deficiencies amply compensated for by enormous, complex eyes that give them a visual acuity unrivaled in the insect world.

Odonates derive their name from the Greek Odonata, meaning “toothed jaw”, as these creatures are fierce predators, both in their aquatic larval stages and as adults, favoring other insects, and occasionally even tadpoles and small fishes. Take a look at the image of a pair of Tropical Bluetails in the “heart” or “wheel position” of final copulation, with the female mating while consuming what appears to be the abdomen of another female Tropical Bluetail!

In fact, mating in the Odonata is a highly variable and, some would say, mind-boggling process. It usually begins with the male grasping the female behind her eyes, in flight, using structures at the tip of his abdomen known as primary claspers (as demonstrated by the pair of orange-yellow Common Citrils). Before making contact, however, the male transfers sperm from the tip of his abdomen to a special storage pouch, located under the base of his abdomen, surrounded by complex structures known as secondary genitalia. Clasped by her neck, the female wraps her abdomen forward until her genital duct comes into contact with these secondary genitalia, and they become locked together at head and abdomen in the “heart position”. After mating, the eggs are laid into water almost immediately, with larva typically taking two to three months of development before they finally crawl out of the water, and emerge as adults, leaving their cast-off shells, or “exuviae” as evidence of their metamorphosis.

Dragon-watching Tips

Across most regions of the world, Odonata flying activity is seasonal, with the first adults hatching from their aquatic larval stages in spring, their numbers peaking by mid-summer, before tailing off in the autumn. When temperatures are cool, Odonata activity tends to be low, so the ideal opportunities for “dragon-hunting” occur on sunny, windless days in mid-summer. Take your binoculars to enhance your viewing, and a digital camera to capture shots that will help you to key out the species once you return home. A recent popular surge in interest for Odonatology has meant that there are now good Odonata field guides for North America, Europe and Australia, as well as a few other parts of the world.

South Africa is home to 164 of the 850 or so Odonata species known from Sub-Saharan Africa, a representative array of which I’ve featured in this blog.

BRILLIANT demonstration of how to make lemonade from lemons!

The photographic detail you captured is exquisite.

The “small world” is most impressive too.

No matter in which direction you look, nature never ceases to amaze!

Jonathan…. can just see a new field opening up for “adventure” travel! What fabulous photos. I passed on the article to Fly fishermen I know. Enjoyed it very much.

Your photos due justice to the vivid palette of these insects. I’m now intrigued to keep my eyes open for Odonata species here in Puget Sound. Sources say there are 19 in WA state, only 3 of which I’ve seen so far.

Thanks for your fresh perspective and wealth of information.