Small Five of Alaska by Kevin Clement

Posted by Kevin Clement

in Of Interest

Anyone who has been on safari in Africa has heard of the Big Five—the five must-see animals, usually listed as elephant, Lion, Leopard, buffalo, and rhinoceros. Other wildlife destinations have emulated Africa and come up with their own lists—for example, most people consider the Big Five of Alaska to consist of Grizzly Bear, Moose, Caribou, Dall Sheep, and wolf. And now my colleague Gerald Broddelez has proposed, and is enumerating, a Big Five of Belgium.

I confess I was never a proponent of Big Five lists, but I am thoroughly enjoying Gerald’s take on the subject. For me, creating checklists carries a danger that the goal of a trip will become the checkmarks rather than the actual experiences, and its success or failure will be judged on the number you can make. For another, they put the focus entirely on big, impressive megafauna, and totally overlook the small, quick, adroit creatures, which are almost always of the greatest importance in the ecosystem. I find that the more-obscure minifauna usually have the more intriguing stories to tell, the most impressive adaptations, the most awe-inspiring techniques of survival.

So I would like to propose a new list: Small Five of Alaska. I don’t intend this as a list of must-sees that anyone should try to check off, but as an indication of the truly awe-inspiring ingenuity of nature.

Boreal Chickadee (Poecile hudsonicus)

I can remember standing outside my cabin in the depths of winter in Denali National Park, at temperatures of 30 or 40 below zero. At such times the air is absolutely still and the hard-frozen forest seems utterly lifeless. And then I remember hearing a stir, a twittering—and suddenly a flock of tiny birds would come flitting and zipping through the trees around me, shaking loose tiny puffs of snow—and then gone just as quickly. And I would stand there in wonderment, asking “How can such a tiny creature survive here?”

A chickadee is the smallest of the handful of birds that remain in Interior Alaska through the winter; they do not migrate. They are scarcely larger than your thumb. And weigh about the same as a pat of butter.

Small size comes with a huge disadvantage in that environment: small things have a greater surface-area-to-mass ratio, and lose heat exponentially faster than large objects. If you put a grape and a watermelon into a freezer at the same time, which is frozen first? And chickadees must maintain a body temperature of 111F—which means there may be a differential of over 150F between their internal and environmental temperatures.

How do they do it? With extra-thick feather insulation (they have four times more feather mass devoted to insulation than to flight) and a roaring metabolism. Maintaining that metabolism takes an enormous number of calories: on a winter’s day, a chickadee can pack on more than 10% of its body weight as quick-burning fat, and then use it up by the following morning. It is as if I, a 200-pound man, were to gain 20 pounds today, and then lose it tonight.

And where do they find all those calories in the winter, when all of their good sources of seeds, buds, insect larvae and eggs, and other provender have disappeared? From the food caches they spent all summer placing all over the forest, in niches, crevices, and holes. It’s called scatter hoarding. A single bird will have collected about a half million objects, amounting to more than 30 pounds.

So, then, how does a bird with a brain the size of a green pea remember where he put all those caches? For one thing, chickadees who live in the Far North develop bigger brains than their relatives farther south—they have more placements to remember. Their brains account for 7% of their body weight…in us, it’s 1.9%. But the really incredible part of the story is that northern chickadees’ brains grow bigger—30% bigger—in the fall, during their time of caching, and then shrink the following spring.

I would really like to think that this is proof that all creatures that live in the Far North are smarter. But I’m afraid that might not be an evidence-based extrapolation. Now, if I could just remember where I put my car keys…

Wood Frog (Rana sylvaticum)

Chickadees go to great lengths to avoid freezing in order to survive the winter. But one of their neighbors survives in exactly the opposite way…by tolerating freezing.

Some small, simple creatures can survive freezing: bacteria, nematodes, some insects. But Wood Frogs are the largest, most complex ones that are able to do it. They have a heart, lungs, and circulation system similar to our own, and should be subject to cell damage from frostbite, just like we are. So what does a Wood Frog do in the winter?

The answer is: not much. Actually, nobody knew the answer until 1972, when a grad student named Michael Kirton decided to find out. He went out on the campus of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in the summer and caught a number of frogs, put radioactive tags on them, and released them.

That winter, he got quite a few strange looks as he walked around campus searching with a Geiger counter. But he succeeded in finding many of his frogs—frozen solid. When he brought them into his warm lab and let them thaw, they started jumping. When he put them back outside, they turned back into frogsicles. Apparently you can do this many times without damaging the frog…although you’ve got to think it must get pretty annoying.

When I met Michael years later, I told him “Don’t you see? You’ve found the perfect pet. You feed it flies; when you leave on vacation, just pop it in the freezer; when you get back, microwave on high for two minutes.”

Since then, Wood Frogs have been the subject of a great deal of scientific study. If we could successfully freeze human organs to preserve them, it would be an enormous boon to medical science. It turns out that frogs do amazing things with sugars.

As temperatures drop, their livers store a huge amount. Then, just before freezing begins, they pack it into their cells. Their blood sugar concentration goes from .0004 gm/ml to 4,500 (4-500 would kill you or me). Their cellular fluid is now too syrupy to freeze. Instead, freezing occurs in the spaces between, drawing more moisture out of the cells themselves…so the sharp-pointed ice crystals can’t puncture the now-flaccid cell membranes.

But here’s the really amazing part. If you give a frog an MRI as it freezes and then thaws, you find that it has the astonishing ability to precisely control its freezing regime. Ice forms first in its feet and legs, then gradually spreads to each organ in succession. Second to last is its liver; and the last to go is its heart, which finally stops beating and solidifies.

When the thawing begins, it proceeds in the opposite sequence, and exactly opposite from what you would expect: the heart thaws first and begins beating, followed by the liver, and so on. The frog thaws itself from the inside out. Legs and feet are last. If you think about it, it has to be that way; if the extremities thawed first, those cells would die without blood circulation to bring them oxygen.

A good motto for a Wood Frog would be: “A Reason for Freezin’: Survivin’ the Season.”

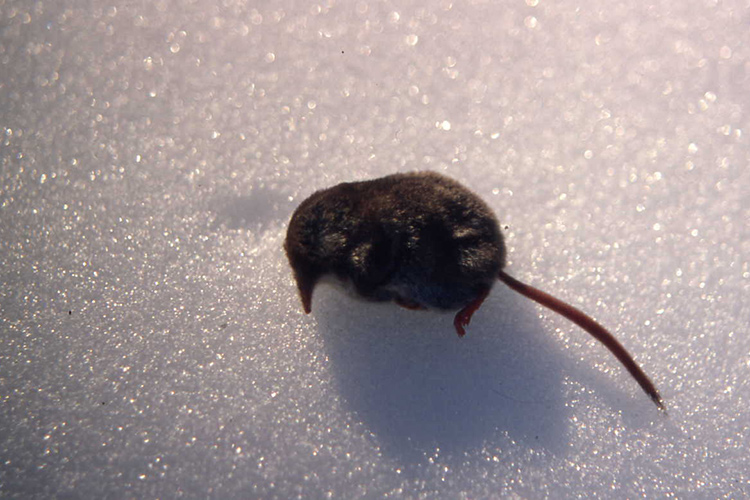

Shrews (Sorex sp.)

Imagine you’re watching a monster movie, featuring a terrifying and voracious predator. It must feed almost constantly, so it is always on the hunt. It moves with blinding speed. It can hunt in total darkness, using echolocation to find its prey. When it strikes, its sharp, needle-like teeth can deliver a bite laced with poison.

Now imagine this creature would fit comfortably within the tiniest of teacups.

What you are picturing is a shrew, one of ten known species that lives in Alaska. Many people who see one mistake it for a small rodent, like one of our voles. Giveaways are the long, pointed snout, which contains the aforementioned sharp teeth, and tiny eyes compared to rodents.

But shrews are not rodents, and in fact are no more related to voles and mice than they are to us. They are Insectivores, along with moles, hedgehogs, and…not much else. They do indeed eat insects, but many other things too, given that they must consume two to three times their body weight every day (which is approximately what I normally eat on an Apex voyage). If they don’t eat, they begin to starve in two hours, due to their blast-furnace metabolism. The heart of an excited or active shrew beats 1,200 times a minute.

Not surprisingly, they often attack animals several times their size, aided by their impossible quickness, and, in some species, by the venom they can inject through grooves in their teeth. They are the only terrestrial mammals that have demonstrated the ability to use echolocation, like bats and toothed whales.

But shrews are tiny creatures. Among them are the smallest mammals in existence, like Alaska’s Pygmy Shrew (S. hoyi) and Tiny Shrew (S. yukonicus)…which weigh about half as much as a penny.

I once had the opportunity to tour the Mammal Department of the Smithsonian Institute, and was introduced to the country’s ranking expert on shrews. I took the opportunity to pepper him with questions, many of which he couldn’t answer—because nobody knows many answers about this obscure and little-studied family. But he did leave me with this sobering thought, a perfect idea for a future monster movie: “If shrews were the size of lions, the world would live in terror.”

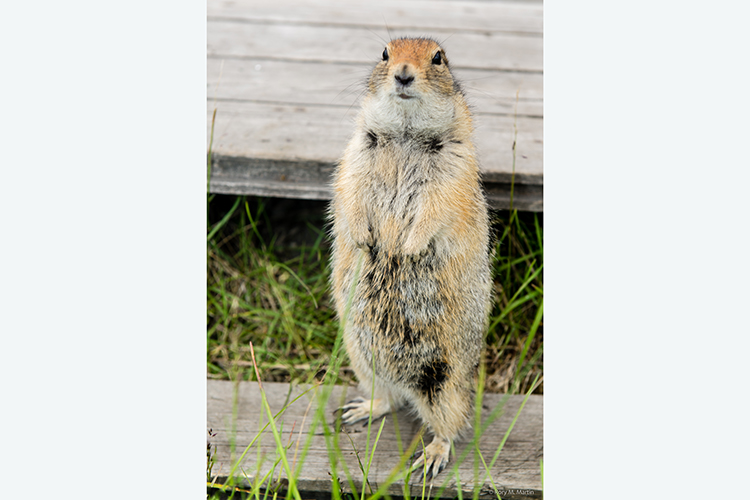

Arctic Ground Squirrel (Urocitellus parryii)

Whenever competitive sleeping becomes an Olympic event, Alaska is going to walk away with the gold. This is because on our side we have the World Champion Hibernator.

The Arctic Ground Squirrel earns that title by sleeping long (eight months of the year) and hard (their heart rate drops to one beat per minute) through the winter. But even beyond that, they manage a trick that not even other deep hibernators can do: their body temperature drops below freezing.

This is not supposed to be possible for a warm-blooded mammal, and thus they are the subject of a lot of scientific study. No antifreeze has been found in their blood, so it’s believed they avoid freezing by supercooling—not allowing any nucleating agents in their bodily fluids that would permit ice crystals to begin forming.

They are the subject of a lot of study by hungry carnivores, too. Many predators specialize in just one or two prey species, but everything that eats meat in Interior Alaska eats ground squirrels, right up to the biggest bears.

I have watched a Grizzly spend 40 minutes vigorously striving to dig a squirrel out of its multi-entranced burrow, virtually disappearing into the huge hole he had created. He must’ve burned far more than the 1,700 or so calories he would’ve gained had he been successful—which he was not. And this happens often. Bears need an occasional protein fix, but their fondness for Ground Squirrel Tartar seems to go well beyond that need. So you’ve got to assume that the little guys just taste really good.

The next time you’re hiking on the Alaskan tundra and you see an AGS—and you will see them, they’re everywhere—try to see it the way a Grizzly does: as something like a 15-inch hotdog with legs. And wish it pleasant dreams.

Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum)

Remember the old Kung Fu TV series? The hero faced tense situations with an unhasty, Zenlike calm. Seeking to walk the path of peace, he avoided a fight whenever possible. But when cornered or forced into it, he struck back with devastating effectiveness.

Well, if Hollywood ever gets around to remaking Kung Fu using Alaskan animals, there is no doubt that porcupines will have the starring role.

Here in the rainforest, we see them almost daily, browsing along the roadside or waddling through our yard. (The guide books say that they’re nocturnal…but apparently ours have never read the guide books.) Unlike most other rodents and most potential prey species, when they are surprised, they do not run (I doubt they could if they wanted to). The most energetic thing they will do is climb a tree. But mostly, if they feel threatened, they simply turn their backs and erect their guard hairs.

Now, Mr. Would-Be Predator, you find yourself facing 30,000 hollow, needle-sharp spines with barbed tips. They are loosely attached, so will easily lodge in your snout, and work their way in over time, which may prove fatal for you. Contrary to folklore, they can’t throw those spines, but your intended victim is now waving his tail around, and will use it to jam them into you if you come too close. Maybe you should go look for some safer prey.

After watching a porcupine for a while, and contemplating what it would be like to be so dangerously armed, a couple of questions naturally come to mind. Q: How could a mother give birth to a thing like that? (A: The babies are born with soft spines, like ordinary hairs. They only harden up after a few hours exposure to air.) Q: How do they ever make babies? (A: They have the muscular ability to rotate the spines. A receptive female cranks hers up out of the way as best she can, and raises up her tail, exposing her underparts…and bingo. Still, one must imagine it would be a prickly business.)

One way in which porcupines differ from a TV Zen warrior: they are incredibly talkative. They must be the most loquacious of all rodents, and produce vocalizations that you would never expect. They serve as the soundtrack for this short video made from footage I’ve taken on walks around the area. And which—who knows?—might one day serve as the pilot episode for Kung Fu II.

Delightful and fascinating. My heart of course is with Gladys, who sometimes features in Ingrid’s posts. Can’t help lovin’ her and her porcupette.

On one of my favored creatures. I never run into them! This was wonderful to watch one in action. What cute sounds!!

This is the first time I have ever heard the melodious sounds of a porcupine…and they have just rocketed up on my list of animals to love! Thanks for sharing that!