How Not to Social Distance

Posted by Marco Tonoli

in Of Interest

In a time where we all find ourselves putting great effort into distancing ourselves socially, I thought it might be appropriate to consider the concept of being social in the natural world. While we are all drawn to search for those rare creatures that survive largely due to their solitary behavior, many species on our planet thrive by being social. Whether it’s to improve their chances as a hunter, to avoid becoming the hunted, or to reap the benefits of co-operative breeding, there are many advantages of sociability. The poster child for communal behavior is a creature that is so social, the word “sociable” was added to its common name.

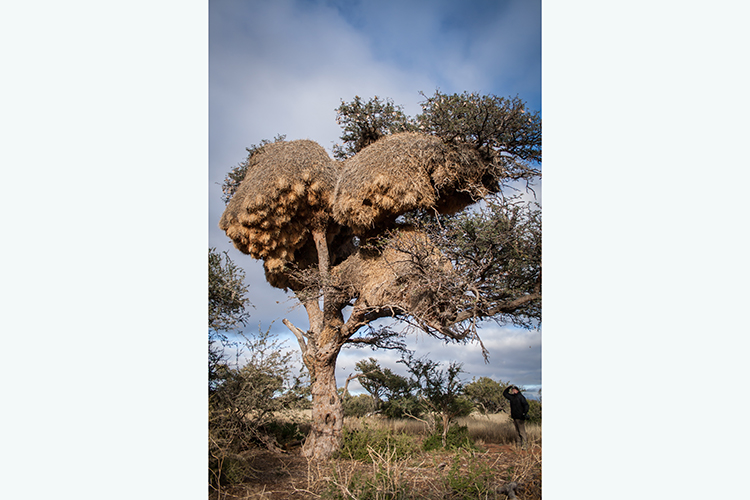

Throughout the arid regions of Southern Africa, nature’s little engineers have taken to the trees. Sociable Weavers, the builders of the largest communal nests in the world, will design and create colossal structures on almost anything that can hold the weight. Colonies of up to 300 birds, all loyal to their own dwelling, build nests weighing up to 2,200 pounds (or 1,000 kg) that house the birds in individual compartments accessed by tube-shaped entrances. Nest-building is an endless task, and these mammoth structures are occupied throughout the year. Occasionally they grow so massive that they may bring down the largest of Camel Thorn trees.

But what is the benefit to amassing to these populations, and why does this strategy seem to make the Sociable Weaver one of the most abundant and successful birds in their harsh desert environment?

Birds’ body temperatures on average are 5.4°F (or 3°C) higher than that of mammals. Small creatures are very susceptible to heat loss and gain. With freezing winter nights and extreme heat in the summer days, Sociable Weaver adults, weighing in at 1 ounce (or 27 grams), would require vast amounts of energy to maintain a constant body temperature on their own. It is therefore vital that these birds master the art of thermoregulation in order to survive in these unforgiving environments.

Bitter winter nights can drop the ambient temperature well below freezing, but the thatch structure traps warm air. On freezing nights the birds huddle together, up to 5 in a compartment, and the thick blanket of thatch prevents their heat from being lost. The difference between interior and exterior temperatures may be more than 41°F (23°C), with a comfortable 73°F (or 23°C) inside the structure on nights with an outside temperature of 32°F (or 0°C).

This behavior allows Sociable Weavers to save up to 50% of the energy they would use to stay warm if they nested alone. This energy savings is the equivalent of over 10,000 insects per day for a colony of 300 birds. With this reduction in food requirements, the desert environment can support much higher densities of this species in comparison to other insect-eating birds.

The reverse effect is achieved during the harsh summer days. While the ambient temperature can range between 61° and 104°F (or 16° and 40°C), the temperature in the interior of the nest will remain between 73° and 84°F (or 23° and 29°C). These more moderate temperatures minimize the cost of keeping a constant body temperature and prevent the use of excessive amounts of water for evaporative cooling.

This is a perfect example of how socialistic behavior and the strategy of building thermal shelters can overcome the harsh desert environment.

Very interesting, informative and educational Marco. Thank you.

Thanks Marco,

They certainly understand thermodynamics! And without the benefit of a textbook. Nature is wonderful. 🙂